Even though the RBA just cut rates by 25bips as I write this article on the 12th of August 2025, I figured it would be time to rethink what we can do about the Aussie Housing market. (I wrote about this back in 2022 as well, but this time I have AI deepthink to assist me).

First off we need to workout what we can do, its effects, and how long it would take for these items to take affect.

1) Fix the supply side (long run, largest effect)

- Build way more homes, faster — accelerate approvals, streamline planning and rezoning (more medium-density along transport corridors), and unlock government land for development. Most analysts agree supply shortfalls are a core driver. ABC

- Address trades/labour bottlenecks — train and accredit more tradespeople, reduce regulatory choke points on construction to speed delivery. (Supply is sticky — it takes years to translate approvals into new dwellings.) Daily Telegraph

- Invest in social and affordable housing — direct supply to renters and low-income buyers reduces competition at the margin and reduces political pressure for short-term investor responses. Alor Blog

-

2) Demand-side tax and fiscal reforms (target speculative demand)

- Reform negative gearing / CGT discount — limiting or redesigning them reduces the after-tax return to property investors and could damp speculative demand. Many think it helps affordability; others warn about unintended rental supply effects. Expect politically charged debate and transitional volatility. The Australia InstituteParliamentary Budget Office

- Replace or reform stamp duty (move to a broader land tax) — stamp duty discourages turnover and inflates prices for buyers; a land tax discourages speculation and is more efficient across the cycle. State policy choices here materially affect demand. The Latch

- Vacancy / short-stay levies and foreign buyer rules — taxes or surcharges on vacant homes, short-stay rentals, or foreign investors can target niche drivers of price pressure in inner-city and high-end markets. Evidence on effectiveness is mixed but it’s being used in some states. ABCApartments.com.au

-

3) Macroprudential & monetary tools (quick to deploy; blunt)

- APRA macroprudential levers — banks can be required to tighten serviceability buffers, cap high-LVR or interest-only investor lending, or raise capital buffers. These reduce borrowing capacity for speculators without changing taxes. APRA already has a toolkit and has used similar measures historically. APRA+1

- Interest rates — higher official rates cool prices quickly but hurt indebted households and the broader economy; this is the bluntest, costliest option.

-

4) Migration and settlement policy (short-to-medium term)

- Pace & location of migration — higher net migration increases housing demand especially in gateway cities; matching settlement to where housing supply/infrastructure exists (regional settlement, targeted visas) can relieve city pressure. This is politically sensitive and interacts with labour market needs. ABC

5) Quick-impact interventions / nudges

- Targeted first-home buyer support (shared equity, guarantees) — helps buyers without driving broad investor demand.

- Better data & enforcement — accurate vacancy registers, faster eviction/tenancy management reform, transparent foreign-ownership data — to design targeted policy.

Trade-offs and risks (be realistic)

- Timing & lags: Supply fixes take years. Tax changes can take effect faster but may cause investor selling and short-term rental shocks. ABC

- Unintended consequences: Removing investor incentives could reduce rental stock or push up rents if investors exit rapidly. Careful transition rules matter. Australian Property Update

- Political feasibility: Changes to negative gearing/CGT or migration policy are highly contested — durable change needs cross-party or broad stakeholder buy-in. Daily Telegraph

What a credible “cooling package” might look like (example, coordinated)

- Short term: APRA tightens investor LVRs/serviceability; states apply vacancy levies and enforce foreign-buyer rules. APRAApartments.com.au

- Medium term: Federal reform of negative gearing/CGT with phased grandfathering; targeted migration settlement to regions. Parliamentary Budget OfficeABC

- Long term: Major planning, zoning and trades-training push + large-scale affordable housing build program.

Key data sources I used

- Investor counts & property counts (industry/ABS summaries): ~2.24 million investors owning ~3.25 million investment properties. Property UpdatePillar Financial

- Number of taxpayers negatively gearing: ~1 million (recent ATO/press reporting). ABC

- Literature estimates of full removal impacts on national prices: studies/analyses generally point to a small national price effect (order of ~1–2.5% fall in prices for a full abolition). I used a midpoint of –2.0% for the "full removal" reference point. The ConversationGrattan Institute

What the model does (brief)

- Uses a simple investor distribution by number of properties (≈72% own 1 property, ≈19% own 2, smaller shares own 3+). Property Update

- Counts the excess properties (every investor’s properties beyond their first) that would be affected by a cap-to-1 rule.

- Applies behavioural sell-rates (assumptions) to those excess properties to estimate how many would be sold into the market. I used conservative baseline sell probabilities:

- 2-property owners: 10% sell their 2nd

- 3-property owners: 20% of their excess

- 4-property owners: 30%

- 5-property owners: 40%

- 6+ owners: 60%

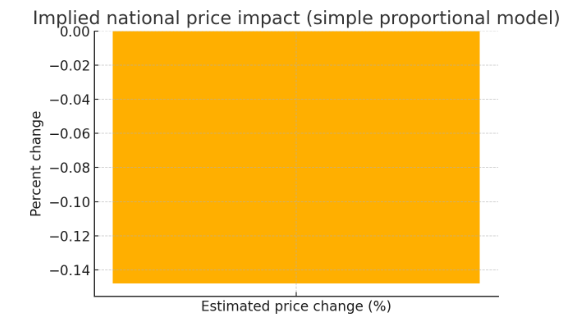

- Scales the literature "full removal" price effect proportionally by the share of investor stock sold to get a very simple national price change estimate.

(You can change the sell-rate assumptions and re-run; I can do that interactively.)

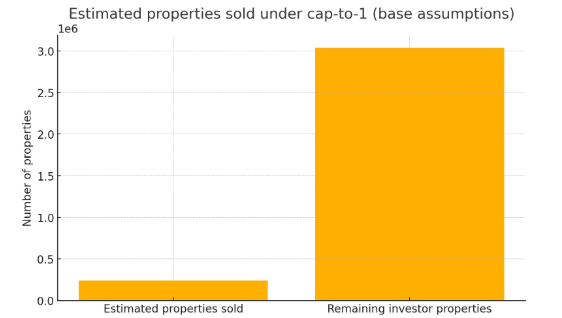

Base-assumption results (from the run you saw)

- Estimated properties sold (one-off, across Australia): ~230,000 (rounded).

- That is about ~7% of the ~3.25 million investor properties (sold share shown in the table).

- Implied national price effect (very simple proportional scaling from a –2.0% full-removal benchmark): ≈ –0.15% (i.e., roughly a one to two-tenths of one percent fall in national prices).

I displayed the numeric summary and two charts (properties sold vs remaining; and the tiny implied price fall).

Interpretation — what this simple model tells you

- A cap to one property mainly affects the minority of investors who hold more than one property (≈28% of investors). Because most investors only hold one property, the policy’s maximum demand effect is limited — and the simple proportional scaling suggests a small national price impact (well under 1% in the baseline run).

- However, the distributional effects matter: if sell-offs are concentrated in particular locations or segment(s) (e.g., inner-city apartments, high-yield suburbs), local prices and rents could move more than the national average.

- Rental market implications depend on whether sold properties become owner-occupied, are bought by other investors, or are withdrawn from the market. In the short run, forced selling could reduce rental supply and push rents up locally even as headline prices edge down.

- The model is intentionally simple and illustrative — it does not capture dynamic general-equilibrium effects, credit re-pricing, timing (sales could happen over months or years), or offsetting policy changes (e.g., CGT changes, state housing supply programs, APRA measures).

Major caveats & limitations

- Behavioural uncertainty — sell rates used are assumptions. Large investors may respond differently (retain, restructure via trusts, sell via corporate vehicles, or reposition portfolios). A small change in assumed sell probabilities changes outcomes materially.

- Price scaling is simplistic — I scaled linearly from the literature’s full-removal price estimate. Real markets are non-linear and location-specific; academic models often show modest national falls but larger local effects. SpringerLinkThe Conversation

- Timing and dynamics ignored — this is a one-off, static snapshot. In reality effects would be phased, with transitional grandfathering, and lenders/potential buyers reacting over multiple years.

- Other tax incentives matter — CGT discount and other concessions interact with negative gearing; modelling them jointly changes outcomes (Grattan/Treasury modelling has done combined packages). Grattan InstituteTreasury